As President Calvin Coolidge once said, “The business of America is business.” America loves enterprise. We view business with esteem and honor, and we strive to emulate it every day. We often see businesspeople as the caretakers of our socioeconomic well-being and as the force that produces the vast array of goods and services available to us. We credit business with creating the most powerful and advanced economy in the world.

As President Calvin Coolidge once said, “The business of America is business.” America loves enterprise. We view business with esteem and honor, and we strive to emulate it every day. We often see businesspeople as the caretakers of our socioeconomic well-being and as the force that produces the vast array of goods and services available to us. We credit business with creating the most powerful and advanced economy in the world.

In our economy, we rarely distinguish between “business” and “industry.” Yet, understanding this relationship is at the core of how our economy truly functions. Business is the mechanism that American society uses to manage the physical aspects of our lives. With industrialization came immense production capabilities and efficiencies. It is business enterprise that manages the many moving parts of the industrial system as a whole. However, over a century ago, American economist Thorstein Veblen showed that our belief in business enterprise as the faithful caretaker of socioeconomic well-being is largely a myth.

Captains of Industry

Veblen observed something distinct in the workings of large businesses as separate from industry. His insights emerged as the American economy shifted from an agrarian and small-scale handicraft base to large-scale industrialization. He called the leaders of this new industrialized economy “Captains of Industry.” These early industrial businessmen created vast wealth by consolidating and controlling their respective markets and industries—oil, railroads, mining, manufacturing, and more.

Veblen’s Theory of Business Enterprise

As the American industrial system expanded and evolved technologically, the mechanisms of business control also changed. Veblen explained this evolving process in his book The Theory of Business Enterprise. He described the phenomenon as follows:

“The material framework of modern civilization is the industrial system, and the directing force which animates this framework is business enterprise.”

He continued,

“A theory of the modern economic situation must be primarily a theory of business traffic, with its motives, aims, methods, and effects.”

Armed with this new definition of business, Veblen dissected the underlying fundamentals of business enterprise and demonstrated how they impact our socioeconomic macrocosm.

Separation of Business and Industry

Veblen recognized a dichotomy between business and industry, rooted in two distinct sets of human behavior. Business, he argued, is driven by predatory, competitive exploitation—what he referred to as “getting something for nothing.” Meanwhile, the industrial system is guided by factual knowledge, physical sciences, and cooperative behavior, all aimed at maximizing efficiencies to meet the broader provisioning needs of society. For business, Veblen claimed, “the end is pecuniary gain; the means is the disturbance of the industrial system.” By “disturbance,” he meant the methods businesses use to control markets, limit production, and raise prices for higher profits. On a societal level, Veblen concluded:

“The outcome of business control of industrial affairs through pecuniary transactions, therefore, has been to dissociate the interests of those men [businessmen] who exercise the discretion from the interests of the community.”

Product Vendibility vs. Serviceability

Pecuniary control over the industrial system was not limited to restricting production or controlling markets. It also required new overhead functions such as branding, sales, advertising, public relations, and legal rights—activities intended to enhance product “vendibility” rather than “serviceability.” According to Veblen, these costs accounted for about half of total product costs.

Tangibles vs. Intangibles

Ultimately, the emergence of new “mega-wealth” stemmed from the financialization of businesses through equities (stocks). These shares were created to monetize intangible assets—such as goodwill, branding, and earning potential—on top of any physical assets already capitalized through other forms of debt (e.g., bonds). By extracting higher profits via limiting production, cutting costs, controlling markets, and harnessing industrial efficiencies, a new breed of businessmen arose: the “Captains of Finance.” They packaged the profits generated by the industrial system under business management as “earnings per share.” These equities became so lucrative that maintaining their value evolved into the primary objective of corporate management. With investment banks providing credit, businesses leveraged debt to inflate their enterprise value even further.

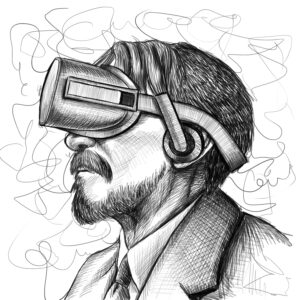

Evolution of the American “Intangible” Economy

The massive shift Veblen foresaw—from industrialization to the financialization of the American economy—has now reached an advanced stage. Over the century following Veblen’s writings, intangible valuations of corporations (through equities) far surpassed the value of their underlying industrial bases. With globalization, corporations could outsource industrial processes to cheaper foreign markets, detaching themselves from physical production. This transition benefited the financial sector and upheld a strong dollar, but weakened domestic industry. While financialization created new “pecuniary” forms of employment (e.g., legal, finance, advertising, sales, marketing), it simultaneously eliminated vast tracts of industrial jobs and skills.

One clear outcome of this change in business modus operandi is the extreme concentration of wealth in fewer hands. Our financialized socioeconomic system now struggles to produce the full range of goods we need domestically. Today, retirement plans, housing, government, and education are all financialized, valued primarily through quantitative, pecuniary metrics rather than qualitative measures. Veblen labeled this new American socioeconomic structure the pecuniary culture.”